Designing a Course Strategy

Before a voyage by sail begins, the wayfinder designs a course strategy and reference course for reaching the destination from the departure point, given the capabilities of the vessel and the winds, currents, and weather conditions anticipated along the way. (See “Winds, Weather, and Currents of the Pacific.”) The course strategy represents the most efficient way of getting to the destination. The wayfinder also chooses the best time to go (when the wind and weather conditions are the most favorable), taking into account the timing of the return voyage as well.

Capabilities of the Vessel

Sailing vessels like Hokule‘a cannot sail directly in the direction of the wind. If it needs to head toward the direction from which the wind is blowing, a vessel will sail off to the side, while remaining as close as possible to the wind direction (i.e., close-hauled), then change tacks to the other side, making forward progress in a tedious zigzaging pattern known as tacking:

Tacking increases the distance and time it takes to get to a destination and is to be avoided if possible. Navigators of sailing vessels tgry to stay upwind or windward of their destinations when they can, so that they won’t have to tack to reach them.

The Reference Course

The reference course designed for a voyage represents the course the canoe would sail given average wind and current conditions and the canoe’s performance capabilities.

It is highly unlikely that the canoe will stay on the reference course because wind direction will vary along the way, and the canoe can only sail in the direction the wind allows it to sail. The art of wayfinding involves adapting to variable and unexpected conditions of wind and weather while maintaining progress towards the windward side of the targeted islands.

The reference course is used as a local longitude line between the starting point and destination. The wayfinder can plot his position east or west of the line as the voyage progresses. If the wind pushes the canoe off the reference course, the navigator usually tries to get back to it, or close to it, when the wind allows the canoe to do so.

The wayfinder’s determines his position east or west of the reference course based on his estimates of the following:

- the speed and direction of the canoe has traveled

- the average speed and direction of ocean currents

- latitude (based on measurements of the altitudes of stars crossing the meridian)

These estimates are made without instruments, and can be hampered by poor weather conditions which obscure the sky and confuse the seas. The speed and direction of ocean currents cannot be measured or even estimated without instruments, so the figures used are seasonal averages rather than actual measurements. The accuracy of the estimates can also be affected by mental fatigue. The wayfinder must track and memorize the canoe’s performance over 2,000 miles and three-and-a-half weeks at sea, while getting as little as a couple of hours of sleep a day. But wayfinding doesn’t require exact positions to be successful. The wayfinder will be successful if he is able to

- keep track of where he is in relationship to his reference course and destination

- guide the canoe to the general vicinity of his destination

- locate land in that vicinity and use known islands and landmarks to get to his destination

Within the limitations of the wayfinder’s estimates, these three things are possible, as the success of Hokule’a in making landfalls in the past has shown.

Hawai‘i to Tahiti

A course strategy can be illustrated using a Hokule‘a voyage to Tahiti as an example. The best time to sail to Tahiti is in the late spring or early summer-in between the storm seasons and the hurricane seasons north and south of the equator in a typical year.

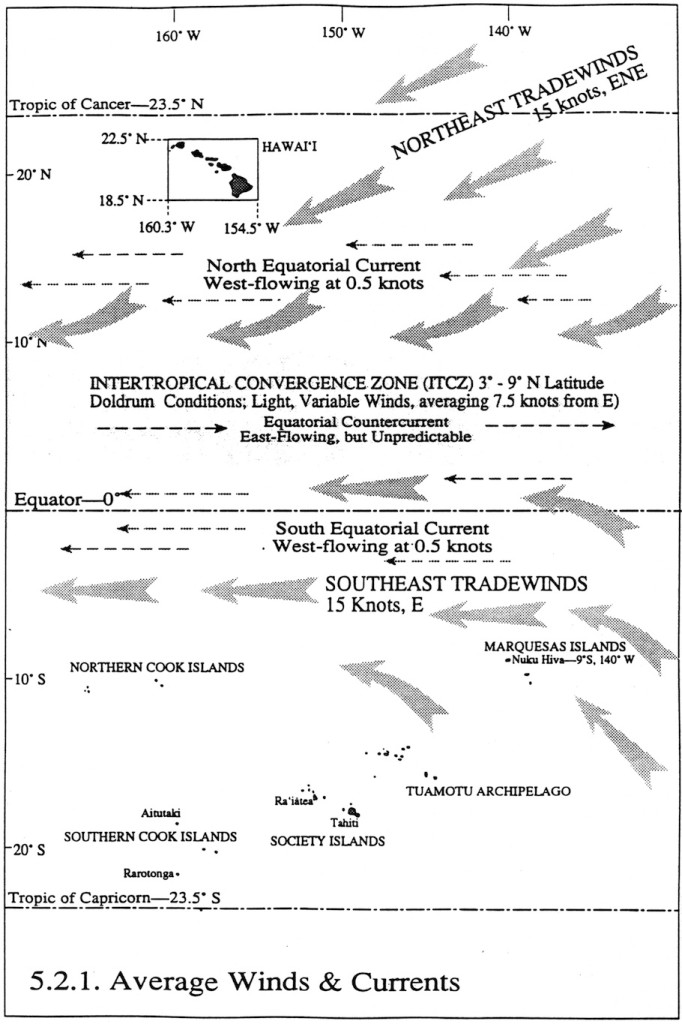

Sailing to Tahiti is a challenge because Tahiti lies to the south southeast of Hawai‘i, upwind and upcurrent, so the canoe must make easting against the wind and current for most of the way. The canoe crosses the NE and SE tradewind zones as well as two great west-flowing ocean current, -the north and south equatorial currents, which can carry the canoe 14-20 miles westward per day.

Voyaging to Tahiti, 1992

On the 1992 voyage to Tahiti, Hokule’a’s reference course line ran SE by S, sailing on a close reach, full and by the wind, until about 9 degrees N latitude or 700 miles from Hawai’i.

At about 9 degrees N, the canoe enters an area called the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ), which lies between the NE and SE trade wind systems (and the west flowing north and south equatorial currents). This region, where the NE and SE trade winds converge, is noted for its heavycloud cover, squalls, light and variable winds, and dead calms, all of which make sailing and navigating less than ideal. The windless weather, a condition known as the doldrums, could stall the canoe for days. The ocean may appear like a lake:

Heavy cloud cover hides the stars, so navigating by the celestial bodies is difficult.

Under such conditions, the wayfinder uses the ocean swells to orient the canoe. However, confused seas in the area, without clear swell patterns, may make steering by the swells difficult as well.

The days of calm and heavy cloud-cover test the patience and intuition of the wayfinder, but the doldrums have a unique beauty: on days when sunlight is diffused in the heavy cloud cover, the sea mirrors the golden light; on clear nights, the sea surface can be so smooth that the stars and constellations are reflected in it; on nights of 100 percent cloud cover, the ocean and sky are pitch black.

In the ITCZ, between the two west-flowing equatorial currents, is the eastflowing equatorial countercurrent, which results from the water pushed west by the tradewinds flowing back east parallel to the equator. This countercurrent could help the canoe gain easting. However, the countercurrent is sporadic and shifting. It is generally weakest in May-June and strongest in September-November, when its speed can reach about 1 knot. Occasionally the countercurrent becomes stronger, as it has in 1992, because of El Ni?o, a weather condition which brings westerly winds to the Southern Pacific and dangerous hurricanes. During the last major occurrence of El Nino, in 1982-1983, Tahiti was hit by six hurricanes.

The canoe tries to get out of the ITCZ as quickly as possible, sailing SSE in the shifting winds.

Once the canoe is in the south east trade wind zone, at about 3 degrees N, the strategy is to sail south against the E to ESE winds, without losing any easting, until the canoe reaches one of the islands in the target screen, which stretches 400 miles E to W from Manihi in the Tuamotus to Maupiti in the Society Islands. If the canoe has enough easting, it will make landfall east of Tahiti and it can head downwind (SW) to to its destination. (Adapted from Will Kyselka’s An Ocean in Mind. Honolulu: UH Press, 1985.)

The actual course of the canoe in 1992 shows the sailing strategies used in the actual weather conditions encountered. The actual track is marked by x’s; the navigator’s estimates of position by o’s:

The navigators held a steady course in the Northeast Tradwind zone down to about 6 degrees N, making easting into the trades (i.e. the actual track of the canoe runs to the right of the reference course), light southerly winds in the ITCZ forced the canoe to tack east. The navigators were fairly close in their estimates of position.

Around 3 degrees N, the canoe tacked west. On July 8, the navigators revised their estimate of their position, placing themselves east of their actual course rather than west of it, though still well east of the reference course. On July 14, they made landfall at Mataiva, fairly close to the mid-point of the screen of islands formed by the Tuamotus and Tahiti Nui, which they were targeting.

Rarotonga to Hawai’i-1992

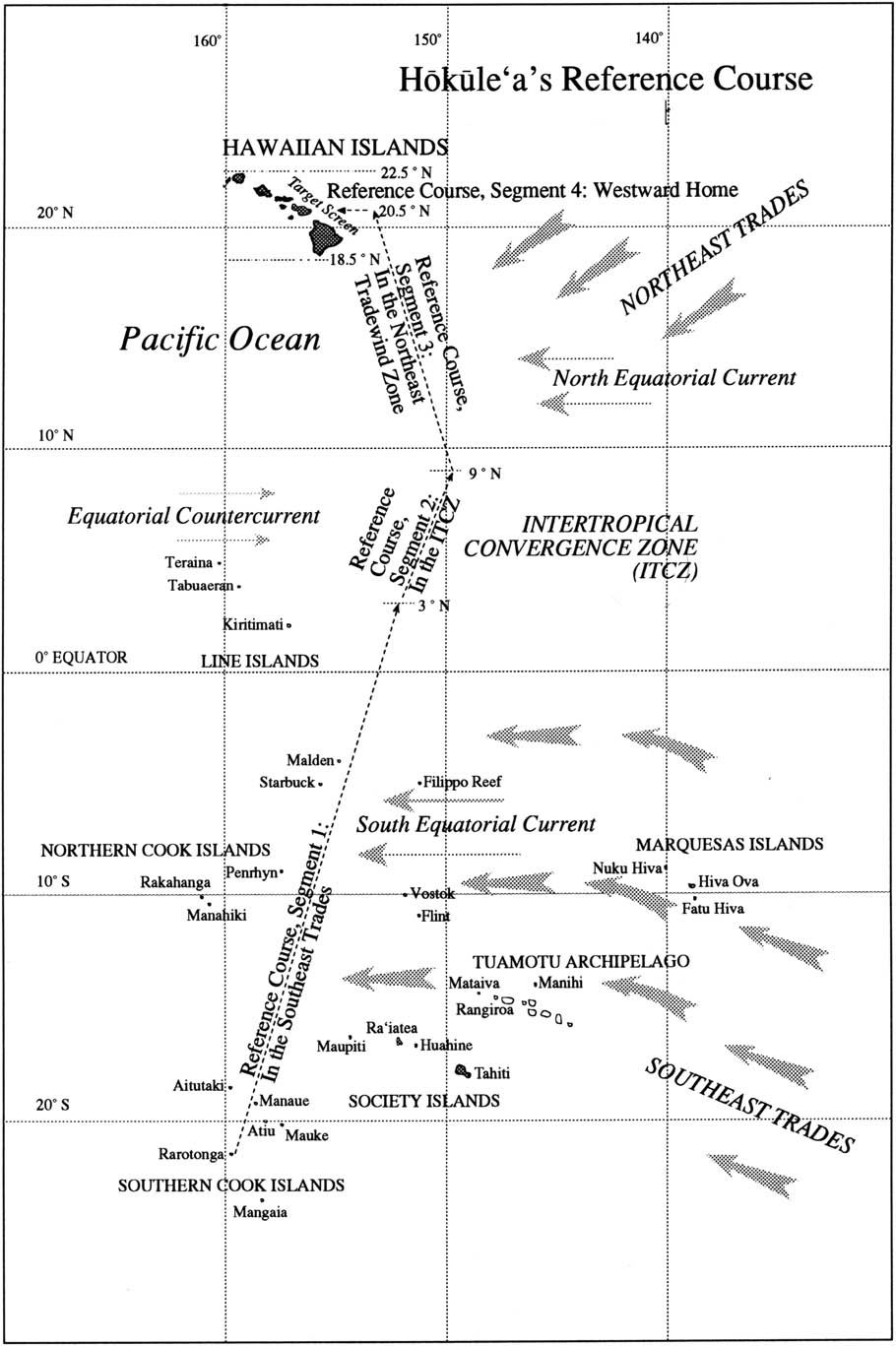

The 1992 voyage home from Rarotonga used the following Course Strategy, designed by Nainoa Thompson:

Starting Point: Rarotonga in the Cook Islands (21 degrees 14 minutes S latitude; 159 degrees 46 minutes W longitude)

Target Screen: The Hawaiian Islands, between 18 degrees 30 min. N latitude (25 miles south of Ka Lae, or South Point) and 22 degrees 30 min. N latitude (16 miles north of Kaua’i), or 240 miles S to N; and between 154 degrees 40 min. W longitude (25 miles east of Cape Kumukahi) and 160 degrees 20 min. W longitude (Ni’ihau), or 340 miles E to W.

Destination: Hilo, Hawai’i

Estimated Length of Voyage: 2,749 miles; about 26 days.

Sail Plan

Based on the average wind and currents between Rarotonga and Hawai’i in November, and the sailing capabilities of the canoe (5 knots or 120 miles per day in 10-20 knot winds,with a windward ability of 68 degrees off the direction of the wind), the voyage was broken into four segements:

Segment 1: In the Southeast Trades. Sail NNE at 5 knots from Rarotonga to 3 degrees N latitude.

Latitudes: 21 degrees S to 3 degrees N

Average Wind Conditions: Southeast trades, from E to ESE at 10 to 20 knots. Current: South Equatorial Current; west-flowing; 0.5 knots; 12 miles per day (0.5 knots x 24 hours)

Average Canoe Speed: 5 knots; 120 miles per day (5 knots x 24 hours); Heading: NNE; Actual heading with current factored in: between NNE and N by E

Total Distance to be Travelled: 1,572 miles (Pre-voyage estimate); Total Time: 13.1 days (1572 miles at 120 miles per day)

Segment 2: In the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ). Sail N by W at 2.5 knots through the doldrums (3 degrees N to 9 degrees N).

Latitudes: 3 degrees N to 9 degrees N

Average Wind Conditions: Variable; generally out of the east; 0 to 10 knots

Current: Equatorial Countercurrent; east-flowing, but unpredictable

Average Canoe Performance: 2.5 knots; 60 miles per day (2.5 x 24 hours); Heading: NNE; Actual heading: NNE (No compensation for current drift. While the Equatorial Countercurrent runs east in this area, it is unpredictable and may or may not take the canoe eastward. However, if the countercurrent is flowing, it will benefit the canoe by helping it to get east of its target of Hawai’i. And if the canoe is in the doldrums for a great length of time, the wayfinder may have to take this east-flowing current into account and reestablish the position of the canoe farther east of the position estimated without compensating for the current.)

Total Distance to be Travelled: 390 miles (Pre-voyage estimate); Total Time: 6.5 days (390 miles – 60 miles per day)

Segment 3: In the Northeast Trades. Sail N by W at 5 knots to 20.5 degrees N latitude, arriving about 85 miles east of the Hawaiian Islands.

Latitudes: 9 degrees N to 20.5 degrees N

Average Wind Conditions: NE Trades, generally from NE by E; 10 to 20 knots

Current : North Equatorial Current; west-flowing; 0.5 knots; 12 miles per day (0.5 knots x 24 hours)

Average Canoe Performance: 5 knots; 120 miles per day (5 knots x 24 hours); Heading: N by W; Actual heading with current factored in: between N by W and NNW

Total Distance to be Travelled: 702 miles (Pre-voyage estimate); Total Time: 5.85 days (702 – 120 miles per day)

Segment 4: Westward Home. Sail W at 5 knots until one of the Hawaiian Islands is sighted.

Latitude: 20.5 degrees N

Average Wind Conditions: NE Trades, generally from Noio Ko’olau (NE by E); 10 to 20 knots

Current: North Equatorial Current; West-flowing; 0.5 knots; 12 miles per day (0.5 knots x 24 hours)

Average Canoe Performance: 5 knots; 120 miles per day; Heading: W; Actual performance with current factored in:132 miles per day

Total Distance to be Travelled: 85 miles (Pre-voyage estimate); Total Time: 0.7 days

Departure

The departure date of October 20 from Rarotonga was determined by two factors. First, to avoid the winter storm seasons in the southern and northern hemispheres. October is ideal because it is in-between the southern hemisphere winter (June-September) and the northern hemisphere winter (December-March) when the probability of encountering storms is greater than at other times of the year. October also falls between the hurricane season in the northern hemisphere (June-September) and the hurricane season in the southern hemisphere (December- February).

Another important factor in setting a departure date is the moon phases during the voyage. The voyage is timed so that there is moonlight at strategic points. A bright moon is desirable while the canoe is in doldrum conditions (around 3 degrees N to 9 degrees N), so the wayfinder can see the ocean swells at night when heavy cloud cover is hiding the canoeguiding stars. An experienced wayfinder can steer by maintaining a consistent pitch and roll in the movement of the canoe; but seeing the swells is an added clue in maintaining his direction.

Moonlight is also important as the canoe approaches Hawai’i because the wayfinder will use the altitude of stars above the horizon to determine his latitude; on cloudy nights with little or no moonlight, the horizon line cannot be seen; moonlight renders the horirzon visible. The voyage from 1992 voyage from Rarotonga to Hawai’i was planned so that the canoe would have a waxing (increasing) quarter moon as it reached the doldrums (approximately Nov. 3) and a waxing crescent moon as it approached Hawai’i (around Nov. 24).

Two other factors need to be met for the canoe to depart on a voyage:

- the canoe and crew have been properly prepared;

- the weather is right, based on (a) meteorological reports (no major storms are headed for the course) and (b) observations of wind direction and speed, the shapes of clouds, and the color of the sky at the horizon at sunrise to determine that good sailing weather would hold for a couple of days.

Islands Along the Way

When the canoe sails out of Rarotonga on a NNE course, the wayfinder is aware of islands along the way, on which he will want to avoid running aground in the dark. Manuae (Hervey Island) is only 15 miles east of the course at 19 degrees 21 minutes S and Aitutaki is 42 miles west of the course at 18 degrees 54 minutes S. The canoe will leave early enough in the day to pass these islands during daylight.

As the canoe continues NNE, it will pass on its port side:

- Manahiki – 10 degrees 23 min. S

- Rakahanga – 10 degrees S

- Penrhyn – 9 degrees S

- Starbuck – 5 degrees 37 min. S

- Malden – 4 degrees 03 min. S

- Kiritimati (Christmas) – 1 degree 52 min. N

And on its starboard side:

- Flint – 11 degrees 26 min. S

- Vostok – 10 degrees 06 min. S

- Filippo Reef – 5 degrees 31 min. S

These islands and reefs represent both a danger and a safety margin. The danger is running aground on one of them in the dark; however, if the wayfinder sights one of them and can identify it, he will know the canoe’s position, whether it is too far east or west of his intended course. Even without sighting the islands, seabirds can be a clue that an island or islands are nearby.

The two most reliable indicators of land are the manu-a-Ku (fairy tern) and the noio (noddy tern), which often fly out at sunrise from their nesting islands to fish in large groups and return at sunset. The general range of the manu-a-Ku is around 120 miles from land, though it can fly farther out and remain out at sea for days, or it can fly back to land in the dark without being sighted. The range of the noio is about 40 miles from its home island.

The Turn West

As Hokule’a approaches the latitude of Hawai’i upwind from the islands (i.e., to the east of it, as his course strategy requires), the wayfinder has to make a major course decision: when to turn the canoe downwind, west toward Hawai’i. Ideally, this turn should be made at 20.5 degrees N (the latitude of the midpoint of the S to N target screen between the Big Island and Kaua’i). The wayfinder determines his latitude by the altitude of Polaris and by the altitude of stars as they cross the meridan. (See “How the Wayfinder Determines Latitude”).

Landfall

The manu-a-Ku (fairy tern) and the noio (noddy tern) will help to expand landfall, indicating the presence of the islands before any island can actually be seen. When the canoe crew sights and identifies any one of the Hawaiian islands, the wayfinder will know exactly where the canoe is and head toward Hilo. Given clear atmospheric conditions, the high dome of Mauna Kea, about 14,000 feet in elevation, can be seen from over 100 miles away; when the dome is obscured by clouds or volcanic haze, visibility is reduced to about 20 miles. If the canoe approaches the Big Island from the SE at night, the first sign of land may be the glow of volcanic activity in Puna.

The 1992 Voyage: Adjusting the Course Strategy Due to Weather Conditions.

On the actual 1992 voyage from Rarotonga to Hawai’i, the wayfinders had to modify the sail plan from the beginning, based on actual weather conditions. Instead of leaving October 20, they waited for winds that would allow them to go east. Southerly winds came on October 26; so instead of heading NNE, the canoe took advantage of the winds and headed E to Tahiti, arriving in Pape’ete on November 1. The canoe again waited for the right winds, and on November 5 left for Hawai’i, heading N by E. Instead of taking just 26 days, the voyage took 35 days (including the 4 day stop in Pape’ete). The crew saw the lights of Hilo town and the beacon from the lighthouse at Kumukahi on the night of November 29; they sighted the Hamakua coast of the Big Island on the morning of November 30.

The reference course (dotted line) for the 1992 voyage from Rarotonga to Hawai‘i, with the actual daily positions (x) and the navigator’s estimates of postion (o) at sunrises.

2000 Voyage from Tahiti to Hawai‘i: Adjusting the Reference Course in Mid-Voyage, Based on the Actual Weather Conditons Encountered

During the 2000 voyage home from Tahiti, Nainoa made a decision to shift the reference course west of the original to allow the canoe to “find the most efficient way home by following a route that the winds allow.” Sam Low, documentor on board, explains his reasoning:

Just before sunset yesterday Nainoa called a meeting with senior crew and navigators and later, after dinner, with the entire crew to discuss a new sail plan. For the last three days we have been struggling to sail the canoe hard into a wind that blows from the ENE and in spite of our best efforts, we find ourselves being forced to the west of our ideal course line. On February 13th we were 35 miles west. During the next four days the numbers mounted 58 , 60, 75 and 110 miles. To make up the distance would require us to continually pinch into the wind, or perhaps even begin to tack. During last night’s meeting Nainoa described a way out of this dilemma. [See the map below: at about 11° S, the track of the canoe (solid line) begins deviating to the left, or west, of the original reference course (dotted line on the right).]

“We are west of our course line and getting more so every day. That is not the result of bad steering on our part, everyone of you has done an awesome job of holding a course. It’s the northerly wind component that is driving us west. The canoe wants to sail free and we have been driving her hard to get back to our course line. We’re not going to do that anymore. What we are going to so is target South Point rather than a point in the ocean 250 miles to the east of the Big Island. That will be difficult and it will require discipline from all of us–but it’s a new challenge. It’s exciting.

Ever since the first voyage in 1976, Nainoa went on to explain, the reference course has allowed for a large ‘cushion’ of error by targeting a point in the ocean 275 miles east of the Big Island at the mid-latitude of Hawai’i (20.5 N) where the canoe would finally turn west down wind to find landfall. During the last 25 years, the ability of Hokule’a’s navigators to use a combination of dead reckoning and celestial clues to find their way over long ocean passages has improved to the point where such an ample cushion might not be needed. Taking that into consideration along with the fact that Hokule’a’s present heading seems destined, it projected forward to bring her directly to the the island of Hawai’i–Nainoa decided to let the canoe find the most efficient way home by following a route that the winds allow.

“When we sailed to Rapa Nui, Nainoa pointed out, “we thought that the canoe was our instrument which we would use to reach land but we found our that in reality we were the instrument for the canoe to reach landfall. It’s something that is difficult to explain. It’s the mana of this canoe. When Max said that he saw land ahead on the day we found Rapa Nui I was a little bit in shock and denial at first. We had been sailing in squalls even worse than we have experienced on this voyage. I stayed back at the navigator’s platform. I didn’t believe it. Bruce had to come back and tug me to go forward–“There it is–it’s there he told me.'”

“I’m not saying that we had nothing to do with finding Rapa Nui–far from it. We trained hard for 2 and a half years for that voyage and we chose a crew of intense, dedicated professionals to make that voyage and we worked every inch of the way. Now I want to do the same thing on this voyage.

This new sail plan will require more precision than any other previous voyage home from Tahiti and so Nainoa has asked Bruce and Chad to assume a more active role in the navigation as assistants to him as they did on the voyage to Rapa Nui.

Note

For the course strategies for the 1999 Rapanui Voyage, see “Plan for the Voyage to Rapanui.”